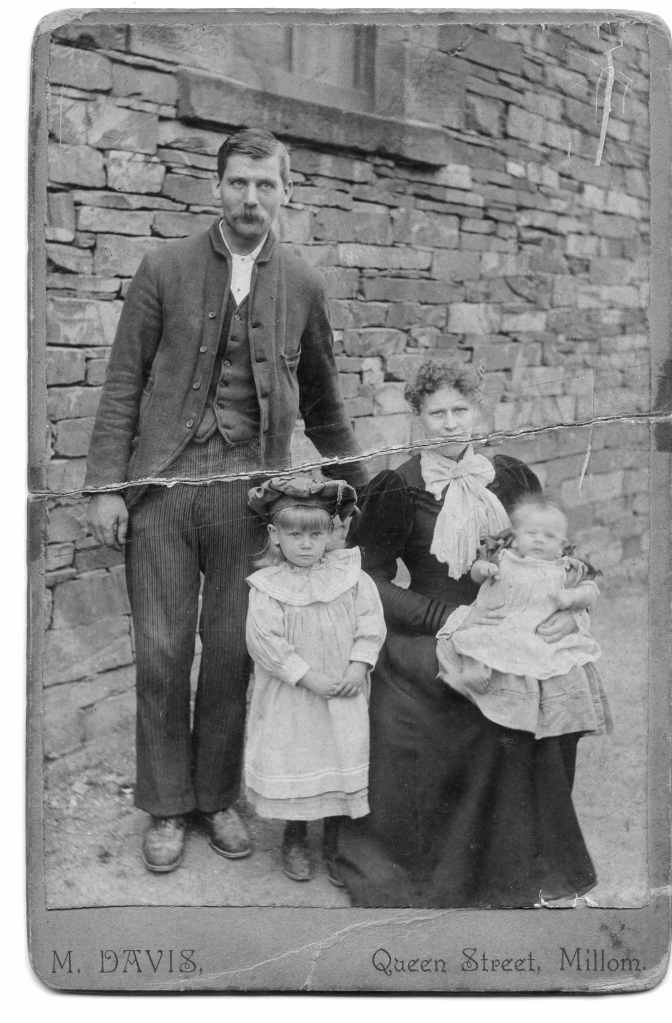

One of the things that I’ve been doing during lockdown is trying to tie up some loose ends in my family tree. My 4xGreat Uncle, Aaron Tyson (1800-1841), had three daughters and one son, but I had no information for any of them after their appearance on the 1841 census at Broughton-in-Furness, Lancashire (now in Cumbria), as Aaron had died just a few months later, aged only 41. Pursuing the lives of his children who were my first cousins, four times removed, hadn’t seemed to be a priority.

I thought I would start with Aaron’s only son, Jonathan Tyson, who was aged seven in 1841 and described as ‘born in county’. His birth was before the start of civil registration, but I found his baptism on 11 November 1833 at St Cuthbert’s, Kirkby Ireleth (Lancashire Online Parish Clerk). By the time of the 1851 census, aged 17, he was working as a farm servant, just outside Broughton. Then he disappeared; I couldn’t find him on any of the subsequent censuses, nor could I find a death for him.

So, I searched for him in the British Newspaper Archive on FindMyPast and found this:

Ulverston Mirror 30 June 1860

“Jonathan Tyson was ordered to contribute 1s 6d per week towards the support of Isabella Askew’s illegitimate child. The parties lived at Broughton, but the defendant has absconded.”

If Jonathan had absconded from Broughton, then I realised I needed to widen my search area beyond the north of England, but I still couldn’t find any trace of him in UK census or death records. A worldwide search did, however, come up with a man of the right name, and age, and from England, living in Pennsylvania in 1870.

Could ‘my’ Jonathan really have absconded that far away from home to avoid paying 1s 6d a week for his illegitimate child?

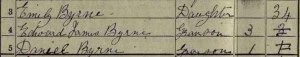

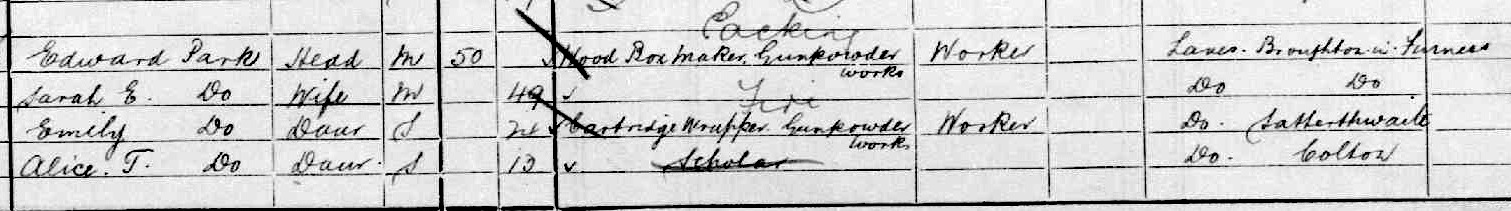

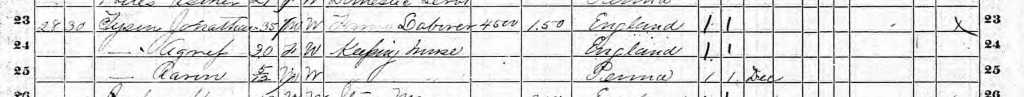

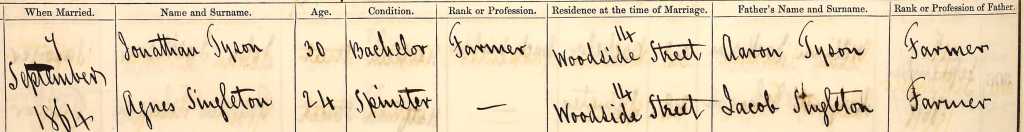

The 1870 US census return shows Jonathan Tyson, 35, living with his wife Agness, 30 and also from England, and an infant son, Aaron, born the previous December. The naming of his son Aaron (Jonathan’s father’s name) suggested that this could indeed be my man. I then found on Ancestry the marriage in Liverpool on 7 September 1864, of Jonathan Tyson, son of Aaron, and Agnes Singleton, daughter of Jacob.

I also found the Pennsylvania death registration of Agnes Tyson, who died on 15 October 1908. She was described as a widow, and the daughter of Jacob Singleton and Hannah Atkinson. I now felt that I had enough evidence to say that the Jonathan who absconded from Broughton before June 1860 was the same man who was living in Pennsylvania in 1870.

If he left Broughton in early 1860 and got married in Liverpool in 1864, he was presumably still in England at the time of the 1861 census, but could have been anywhere in the country. The best option that I can find for him is a John Tyson, aged 27 (which would be the right age), from Lancashire, working as a shipwright in Tower Hamlets, London. This might not be Jonathan, but I suspect that it is. In 1861 his future wife, Agnes Singleton, a 21-year old Dressmaker, was living with her widowed mother, Hannah, in Broughton-in-Furness, but she and Jonathan must have already known each other and sometime between 1861 and 1864 they both made their way to Liverpool, where they were married in September 1864.

On the 1900 US census Agnes claims to have immigrated into the country in 1864 so the couple may have sailed from Liverpool soon after their marriage but I haven’t yet been able to find any evidence of their journey from England.

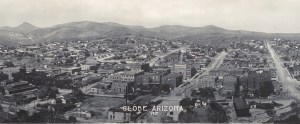

By 1870, when the census (image above) was taken, the family was living in Dartlington in Beaver County, Pennsylvania. Jonathan was described as a ‘Farm Labourer’ and Agnes as ‘Keeping House’. They had with them their son, Aaron, who was five months old, with a note that he had been born the previous December. Aaron’s place of birth was ‘Penna’ – Pennsylvania.

By the time of the 1880 census the family was registered in South Beaver Township. Jonathan was described as a Farmer while Agnes was still ‘Keeping House’, but their 11-year old son has changed his name from Aaron to William. At first I thought Jonathan and Agnes must have had two sons but the 1870 census says that Aaron was born in December 1869 and when William married he gave his date of birth as 29 December 1869. They could have been twins, but neither census has two identically-aged boys; each has only one. When he married Maggie B Gesner in 1891, and on later census records, William always gives his name as ‘William A Tyson’ so presumably he was really ‘William Aaron’.

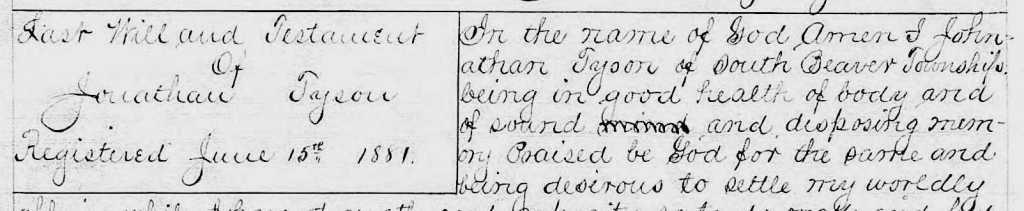

I haven’t been able to find the exact date of Jonathan’s death but his will is available on Ancestry.

The will was written on 24 December 1880 and leaves his land, livestock and ‘implements of farming purposes’ to his son, William and his household goods, furniture and ‘all of my money in Bonds, mortgages or money at interest’ to his wife, Agnes. The will was sent for probate on 15 June 1881, so Jonathan must have died between 24 December 1880 and that date. He was only 47.

Most of the schedules of the 1890 US census were destroyed by fire in 1921, and Pennsylvania is not one of the states for which records survive. By the time of the next census in 1900 William, his wife and five children were still living in Beaver Township, as was Agnes, though her entry on the record is curious as she is living six households away with William and Mary Waggle but is described as ‘mother to family 9 above’. She was a ‘widow’ and ‘Housekeeper’.

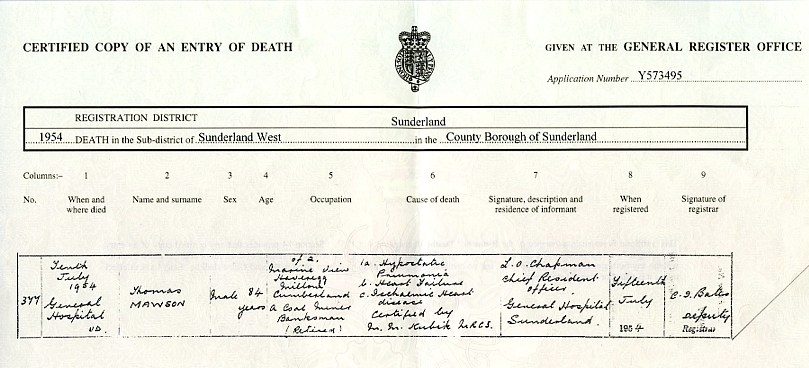

Agnes died, aged 69, eight years later, on 15 October 1908. Her occupation on the death certificate was given as ‘Decrepit’ and the cause of death ‘General Debility. Gradually Failed’. She was buried two days later in the local Seceder United Presbyterian Cemetery.

I always wonder how much people like Jonathan and Agnes kept in touch with family and friends back in England. It would seem unlikely that Jonathan would have had any direct contact with Isabella Askew and the child she bore; the cause of his original abrupt departure from Broughton-in-Furness, but perhaps he heard from others that his daughter was baptised Elizabeth on 1 July 1860. She and her mother, Isabella, were living with Isabella’s parents at the time of the 1861 census, and Elizabeth stayed with her grandparents after her mother married William Herbert on 5 December 1863. Theirs was a short marriage, marred by many deaths. They had five children between 1864 and 1874 but only their youngest son, Thomas, lived to grow up; the others all died before the age of six. In 1875 William died, leaving Isabella a widow at the age of 41 and with two sons, then aged four and one, to bring up alone. Only four years later Elizabeth Askew, the daughter of Isabella and Jonathan Tyson, died, aged only 19, and was buried on 18 September 1979. Her mother, Isabella, died, aged 45, two months later and was buried on 3 November 1879.

One final thought: when I was trying to identify records for Jonathan in Pennsylvania, it took some time as there was another Jonathan Tyson living in the same area and about the same age, so I had to look at his records to sort out which Jonathan was which. I also came across another Aaron Tyson. Both Christian names occur regularly in this one of my Tyson lines (Tyson is a very common surname in Cumberland and the Furness area). It made me wonder if someone else from Jonathan’s family had emigrated to Pennsylvania, maybe a generation or two earlier, and if that was why Jonathan and Agnes had settled there. Something else to investigate!